read more

School education and learning in Judaism

"If you have created children, instruct them at all times, however, do that gently. Spend all you have to buy them books, and keep a teacher for them from their earliest years.Pay the teacher generously; what you give him, you give to your son. And know that your happiness will be increased by your children, and that their welfare will be yours. Let your sons learn skills; It will do them good for the future. Until you have gained wisdom and insight yourself, keep the company of experienced men, and do not be ashamed to learn and to ask. Be the tail of the wise, and you will one day become a leader. But wisdom is walking in the ways of faith, fearing God and shunning evil, that is insight. Learn wisdom, and if it is difficult for you to understand, at least learn mathematics and read medical books."

(from: "Musar Haskel" by Gaon Hai ben Sherina (939-1038); quoted from Alfred Pfaffenholz: What does the Rabbi do...? Judaism, Munich 1995, p. 148)

This quote from a famous rabbi, which is about one thousand years old, is an indication of the great importance that learning, parenting and education in Judaism has. Learning was never reserved for a few - e.g. the priests - but was a general goal. Even the Jews of Eastern Europe, who lived in almost unimaginable poverty: they often could not afford to eat properly, went barefoot until autumn, had only one pair of boots for the whole family to wear in winter, but they paid a teacher for their sons, who often taught them to read, write and pray in Hebrew from the age of three. This sacred duty of Jewish families results from a rather insignificant verse of the Torah: "Teach them to your children, talking about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up." (Deut. 11:19).

In the Jewish religion, in addition to the Torah, there are the Mishnah and the Gemara as rabbinic interpretations, and interpretations of the Torah, which make up the Talmud. There it says in an old commentary of a rabbi: “Your sons but not your daugthers….Thus they say: As soon as the boy begins to speak, his father speaks to him in the sacred language and teaches him Torah. If he does not speak to him in the holy language and does not teach him Torah, it is as if he buries him."

The obligation to teach therefore originally rested with the father; but if he was unable to instruct the son, he had to ensure that a teacher fulfilled the task for him.

Another thing is shown: only boys had a "right for education". This did not apply to girls. However, many families who could afford it also provided education and training for their daughters. At the beginning, the mother educated her daughters at home, and especially during the so-called "emancipation" period, which began with the Enlightenment era and resulted in the "Napoleonic era" with the introduction of many principles of freedom, daughters were also sent to public schools.

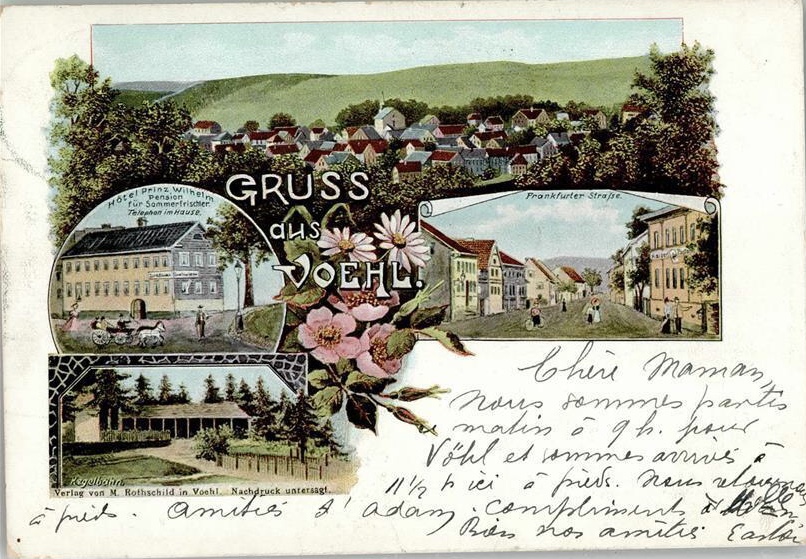

Education for Jewish children before 1827

It is still unknown since when Jewish children in Vöhl were taught by a Jewish teacher. In Vöhl records, "the Jewish schoolmaster" appears for the first time in 1799. We neither know his name nor how many children he taught. It is possible that he only gave religious instruction and that the children otherwise went to the Protestant school, but it is quite possible that at the end of the 18th century Jewish children were not yet admitted to the Christian school or that they were charged special fees, which could have led to only a few of them attending the school. But none of this is known to date.

In the district of Vöhl in the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt, Jewish children were also allowed to attend school free of charge following the occupation by Napoleon's French troops and the introduction of freedom rights in 1825. What this meant, however, was attendance at the state school. Only in religious education were they usually allowed to have their own teacher. This was probably also the case in the Jewish community of Vöhl, Basdorf, Marienhagen and Oberwerba.

In June 1824, a letter from the Grand Ducal Hessian Church and School Council was made public in Vöhl by Mayor Küthe, according to which the connection of a shepherd with that of a school teacher was forbidden. (The shepherd had to kill animals in the ritually prescribed manner so that it could be eaten afterwards). The teacher was allowed to be the precentor in the synagogue at the same time, and the precentor was allowed to exercise the office of the shepherd, but the teacher was no longer allowed to slaughter. The fact that this notice was announced in Vöhl suggests that there was a Jewish teacher at that time. There was probably even someone in Marienhagen who taught Jewish religious education, because on February 1st, 1826, Vöhl's district administrator Krebs wrote to the Marienhagen deputy Klein that he would have to fine him 10 guilders because the above-mentioned order was not being followed in Marienhagen.

As late as October 19th 1827, District Administrator Krebs reported to the Church and School Council in Giessen that all Jewish communities in the district, i.e. "Vöhl, Basdorf, Höringhausen, Alt-lotheim, Marienhagen, Eimelrod", sent their children to the Christian elementary schools. From these various documents it can be concluded that the children were indeed taught together, and were only separated when it came to religion.

From this we can see that it was quite common for the teacher to also have the function of the precentor or priest in the service, to celebrate the bar mitzvah of the boys, the weddings and funerals, but also to perform the office of the shepherd, who slaughtered the sheep, goats or cattle at the numerous Jewish butchers according to strict ritual rules. In 1825, a order was issued by the Hessian Church and School Council in Giessen, which placed poorer Jewish children on an equal footing with poor Christian children with regard to exemption from school fees.

Why was there a jewish school in Vöhl?

Some general reasons for the establishment of a Jewish school have already been mentioned:

- the religious obligation to teach the sons something about the Torah and Talmud;

- related to this: the great respect that education and learning enjoyed, especially among Jews;

- the introduction of freedom and equality rights at the beginning of the 19th century.

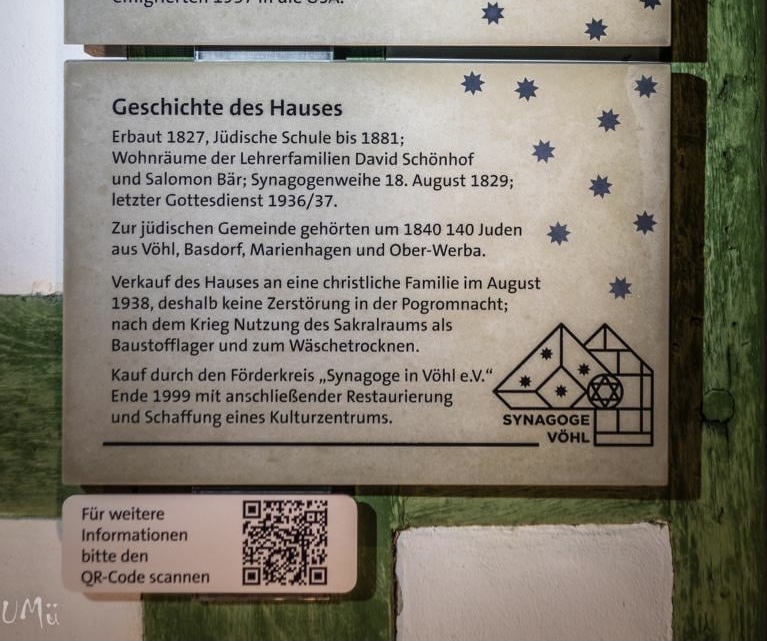

In addition to that, there was a large increase in Jewish population in the district of Vöhl in the 1920s and 1930s. By 1840 the Jewish community had grown to about 140 people, which corresponded to a percentage of about 20% of the population in Vöhl alone. The growing numbers combined with the freedoms granted created self-confidence among the Jews: We are somebody! We no longer need to hide! We can claim the same rights as our Christian neighbours. During these years, various institutions were created; apart from the school, these included the synagogue and then, soon after, the Jewish cemetery.

However, one could now question why there had to be a school with religious focus. Couldn't the Jewish children go to the normal primary schools just like the other children?

As already mentioned, this was the case until the Jewish school was built in Vöhl. The Jewish children attended the school together with the Protestant children; only the subject religion was taught separately. This was also the intention of the government. The Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt wanted to control what was taught in the schools. The government had to ensure the quality of teaching and the comparability of school-leaving qualifications. And this was only possible if the government hired the teachers and controlled the teaching content and the performance of the teachers through the school councils.

Moreover, there was great distrust towards the Jewish teachers, who were accused of being "strict Talmudists", or even rabbis, whose teachings included lying to and deceiving the "goy", i.e. the unbelievers.

However, the joint teaching also created difficulties. The Christian children were taught from Monday to Saturday. The Jewish students, however, could not be expected to attend classes on Shabbat. The different holidays throughout the year also prevented them from working together. The crucial factor, however, was certainly that all subjects in primary school were very strongly religiously influenced. Reading and writing were learned with the help of the Bible and other religious writings. Songs by Martin Luther or Paul Gerhardt were sung, and the poems that had to be learned also came from the Christian-dominated Western culture and tradition. School supervision was exercised not only by the school board but also by the Protestant pastor. In view of all this, it makes sense that Jewish parents tried not to send their children to public schools.

For secondary schools, where the focus is more on specialised instruction, this question was not raised in our area. Jews from Vöhl sent their sons to the secondary school in Korbach, which will be discussed later.

The construction and financing of the school in Mittelgasses

The school constructed in 1827 in the Mittelgasse 9, Photo: Kurt-Willi Julius 2004)

The school constructed in 1827 in the Mittelgasse 9, Photo: Kurt-Willi Julius 2004)

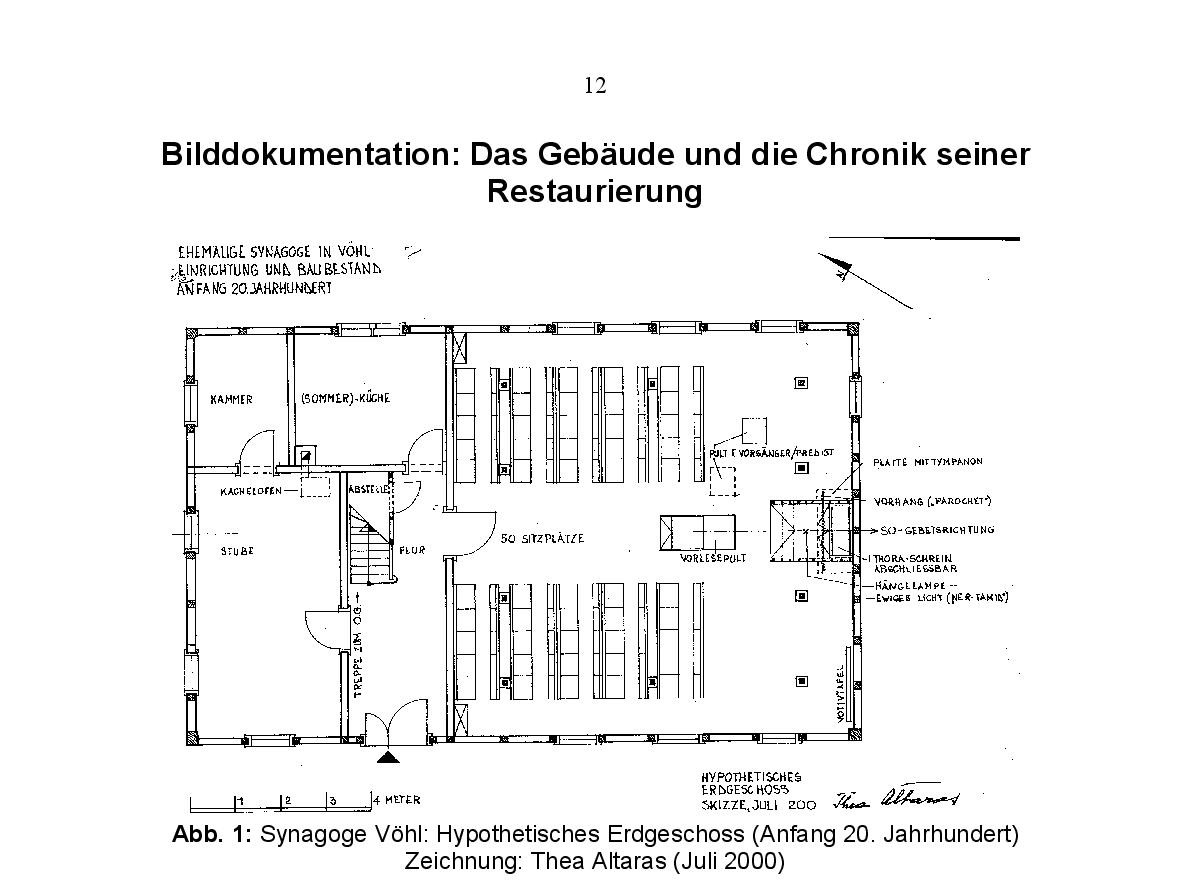

According to the inscription on the beam of the Vöhl synagogue, the building was constructed in June 1827. A synagogue was probably planned from the beginning, but the house initially served as a school, as we know from several documents. In spite of these documents, it is very unclear how intensively classes were held in this house at the beginning. As late as October 1827, the district of Vöhl reported to the school board in Gießen that the Jewish children in all the villages of Vöhl were being taught in the public primary schools. A letter from November of the same year shows that the school was already in use. However, there are also various documents from the following years - until 1835 - which suggest that the Jewish children still mainly remained in the puplic school and were only occasionally taught by a Jewish teacher in the synagogue.

The document mentioned, dating back to November 1827, deals with a conflict between the Jews of Vöhl and Marienhagen on one side and those from Basdorf on the other. Now that it was a matter of paying for the building, the family leaders from Basdorf no longer remembered the agreements made previously. One could not remember ever committing to anything; another said that the Basdorf community had grown so much in the meantime that one had to think about a school of one's own; a third added that he was too old to still use the school and that he had definitely not made a commitment in the past. And then several referred to the rich Ascher Rothschild, who allegedly paid less than he had promised before.

Teacher David Schönhof

The first mentioned Jewish teacher was called David Schönhof and came from Altenlotheim. Possible family relations to other Schönhof families from Vöhl and Marienhagen are not known to date. He had been teaching occasionally in Vöhl since 1827. In 1835 the Jewish religious community wanted to employ Schönhof permanently, both as a teacher and as a precentor for the services. A contract was drafted between the community and Schönhof, which included his employment for life and the question of his salary. As a teacher he was to receive a basic salary of 200 guilders and in addition to that so-called "new moon money" from each pupil, and a school fee from the Jewish community. All family leaders from Vöhl, Basdorf and Marienhagen signed the contract together with Schönhof. The community then turned to the school board in Giessen and demanded that Schönhof be employed as a teacher. The school board had a hard time. Because of the legal situation, he could not refuse to admit a Jewish school. But the fact that they even took the selection and hiring of the teacher in their own hands and explicitly formulated that the financial promises of the Jewish community would only apply to Schönhof's person went a bit far for him. The letter from the board of the Jewish community of Vöhl, probably drafted by Schönhof himself, suggests that the community leaders were primarily concerned with the services and the organisation of ritual acts at the time of circumcision, bar mitzvah, wedding or death, while Schönhof was just trying to secure his existence.

The school board's reply stated that it was also in the interest of the Jewish community not to simply tolerate making any person a teacher. The goal must be good teaching that allows the students to receive a good education, and therefore the government must decide who the teachers should be. In addition, the school council was disturbed that the creation of the teaching position was tied to Schönhof's personality. If a school was to be established, then this should be done regardless of specific persons. The final hiring then took place by decree of the Grand Duke Ludwig at the end of 1836. The headmaster of the school became Selig Stern. Subsequently, the mayor, the Protestant pastor and two Jews chosen by the mayor and pastor were members of the committee desiting about his employment.

David Schönhof lived in the school and synagogue building with his family. In 1840 his family consisted of 3 persons over and two persons under 8 years of age; he also owned a sheep or a goat, probably keeping it in the small stable in the cellar. We do not know exactly where he taught; if he did not teach in the sacred room, then he did so in one of the rooms he stayed in. The room to the left of the entrance door seems the most suitable. However, the number of children was so large that it would certainly not have been possible to teach all the children in this room at the same time. Either there were two classrooms at Schönhof's disposal, or he taught the children - perhaps separated by boys and girls - at different times.

Schönhof did not remain a teacher in Vöhl for the rest of his life, as the contract intended. At the beginning of 1841 he announced to the Vöhl district council that the funds granted to him by the Jewish community would no longer be enough to heat the schoolroom. At the time the contract was signed, a certain amount of firewood had been made part of his salary. That amount, however, would have never been enough. But because of how low the cost of wood was, the Jewish community provided him with a larger quantity. But now the community is no longer willing to provide this additional service because the cost of wood has increased dramatically. According to him, the district council should assure that the Jewish community would supply the necessary wood; otherwise he would no longer be able to heat the schoolroom to the required level. We do not know what happened to this complaint. In the course of 1841, however, Schönhof stopped working as a teacher. His successor Salomon Baer wrote in the school chronicle, which was started in 1878, that Schönhof had been offered a teaching position in Oppenheim on the Rhine.From 4 December 1839 to 1 April 1841, this post was held by Salomon Baer, who was then appointed head of the Vöhl school.

Teacher Salomon Baer

After receiving the certificate of appointment from the sovereign in November 1841, he was the sole teacher of Jewish children in Vöhl for 40 years. He taught whole generations of students during this long period. In addition, Baer served as precentor and, for a time, as accountant of the Jewish community. As a co-founder of the bowling casino society and as a tutor for the children of officials in Vöhl, he quickly became one of the town's important figures. Born in Wimpfen, he attended higher education and then a teacher training seminar in Friedberg. The Protestant church book reports that he passed "the qualifying exams with excellent results" and calls him an excellent teacher; and since the pastor took part in regular inspections of schools, one can certainly believe that he had the necessary knowledge for such an assessment.

Baer's wife Minna, née Liebmann, was probably the sister of Salomon Liebmann from Vöhl. Anyway, there was a proven relationship between Salomon Liebmann and the Baers. Salomon Baer took over the guardianship of Liebmann's son Emil, probably because Emil was a son from his father's first marriage; and furthermore, in 1881 it was Salomon Liebmann who reported Baer's early death to the registry office. It is possible that Minna was the reason for Salomon Baer to come to Vöhl. However, it is also possible that Baer didn´t meet his future wife until he arrived in Vöhl.

By the way, Baer took over further guardianships. When Abraham Kaiser died and left behind four children from his second marriage, he was willing to take care of them. How labor-intensive such a guardianship was can be seen from the fact that Salomon Baer had to write an annual report for Emil Liebmann - there are no such documents for the other guardianships - in which he described the development of the child. Baer's obligation did not end until Emil had completed his training as a merchant in southern Hesse.

Salomon and Minna Baer had four children, one of whom died in infancy, the eldest son when he was about 20 years old; he had probably been rather weak. Baer also took his younger brother into his home, when he came to Vöhl to recover from illness, probably taking advantage of his brother's kindness.

Salomon Baer's first years in Vöhl included the major renovation of the synagogue and school building. We have records of the various workers and contractors who were involved, and we know the expenses of the renovation. But unfortunately we do not know exactly what work was done. A report from the government in Giessen states that the condition of the building was so bad that it would be cheaper to tear it down and rebuild it. It is mentioned that the floor and walls had settled because of the closeness to the river. It is also possible that the ceiling of the main room was removed and the women's gallery was built. At least, the former synagogue room gives the impression that it was not a two-story room from the very beginning: Beams seem to be cut off; the metal cross for the chandelier in the center of the room may also have been inserted to replace beams that were there before.

From Baer's time as a teacher and precentor dates a list of the property of the Israeli community, from which one can conclude the furnishings of the schoolroom as well. There were five benches, five desks, two blackboards and ten so-called lute and reading boards.

In July 1847, the government of the Grand Duchy of Darmstadt issued a law on Jewish schools. The language of teaching was to be German. Whether such a school would be established was a matter of the Jewish community alone, since the children had the option of going to the public school. The political community, though, would have to contribute to the costs if it had also done so for the other school. However, it was forbidden for non-Jewish children to go to the Jewish school.

In the 1960s, there was a conflict over the teaching of Hebrew. Due to state decrees, this was reserved for higher educational institutions. But the community in Vöhl wanted these lessons for their children. Baer did not want to do this for a normal salary, but wanted a special payment for the instruction in Hebrew.

At the end of 1867, a more detailed exchange of letters took place. Selig Frankenthal complains that his three children attending the school are beaten with a ruler by Baer's son Adolph and his foster child Emil Liebmann when Baer is not present, which often happens. Baer justifies himself with being overworked. Since the summer he had to teach in the Christian school as well. And because his precentor duties were very busy during the holidays in the fall, he could not fulfill all of his teaching obligations. In addition, he admitted that he wanted to blackmail the board of the Jewish community a little. The broken stove had not been repaired despite winter temperatures since the board wanted to save the money. And because the children of the board members were now attending school, he had sent them home because of the freezing temperatures in the classroom - in the hope that this would soften their parents.

From 1871/72 there is a report on the inspection of the school and lessons. School inspector Meyer from Höringhausen visited the classes together with pastor Saugmeister (?), school board member Schönthal, teacher Sandlos and district administrator Vorwinkel. At first, it was about the teacher's salary. Baer received just over 232 Thaler a year, including an old-age allowance; since he also gave private lessons, the school inspector thought that Baer had a "sufficient income" despite the expensive living costs.

After Salomon Baer died on June 1st, 1881, the Jewish students of Vöhl initially attended the Protestant school led by teacher Sandlos until February 1st, 1882, during which time Sandlos received a special bonus of 300 Marks.

The school in the Ackerrijje

Haus Rothschild, Arolser Str. 8, Photo: Kurt-Willi Julius

Haus Rothschild, Arolser Str. 8, Photo: Kurt-Willi Julius

Around 1836, Ascher Rothschild built the large house in today's Arolser Straße, formerly called "Ackerrijje" because of the large farms in this street. In the same century, but in a year that is not known yet, the Jewish school moved there. Perhaps this happened after the death of Salomon Baer, as from that time on the living quarters in the synagogue building were no longer occupied by Jewish teachers, but by members of the Mildenberg families up until 1938.

After Baers' death, Emanuel Katzenstein, who had been appointed by the board of the Jewish community in Vöhl, traveled to Münster in Westphalia to find a suitable teacher candidate. Director of the seminary Dr. Steinberg suggested Joseph Laser. Katzenstein visited Laser at his home in Neheim an der Ruhr on Thursday, December 1st and invited him to travel with him to Vöhl immediately to hold a service and lecture on the following Sabbath. Joseph Laser accepted the invitation, introduced himself to the board of the Jewish community and was then recommended by them to the Royal Prussian Administration Office to fill the school position.^2

On January 25th, 1882, Laser received the order of appointment as teacher and cantor from the royal government in Kassel. ^3

On February 1st he was appointed by the pastor and local school principal Sessler (? ) ^4 and on February 2nd he was sworn in by the district official Engelhard in Vöhl.

On January 24th, the local school inspector visited the lessons in religion and mathematics.

^2Source: The Jewish Historical Archives, Jerusalem, 8273/3 (school chronicle, written by Laser himself).

^3 The teacher Bär had still been hired by the government in Giessen; Laser was now in charge of Kassel. This change was related to the political changes that had occurred in the meantime for Vöhl. Until 1866, the Vöhl district with its approximately 20 villages belonged to the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt. In the war between Prussia and Austria in that year, Hesse-Darmstadt had supported Austria. After Prussia's victory, Hesse-Darmstadt had to surrender the Vöhl district to the victor. Vöhl was now assigned to the Prussian district of Frankenberg, but for 20 years it retained a certain independence in some matters as the " Office of Vöhl".

^4 The name cannot be clearly identified. Even a complete list of Vöhl pastors since the Reformation does not mention a name for the year 1882. Possibly the position was vacant and was served by a pastor from a neighboring community.

On June 15th, the local school inspector visited the classes for the second time and informed on this occasion that the teacher was not allowed to offer lessons beyond the scheduled lessons.

On July 5th, from 8 to 11 a.m., the first real school examination took place by the local school inspector, who expressed his full satisfaction; a follow-up examination by the head school inspector Meyer from Höringhausen took place on July 10th.

On July 18, "at exactly seven o'clock", the local school inspector checked the punctual start of classes. Exactly one week later, he checked the school chronicle and informed about the beginning of the 14-day summer vacation on August 7th. On November 15th, he checked the students' performance in reading and noted significant improvements among weaker students. He also warned against reading the Hessian school newspaper. He justified this with an article issued in the edition 39/1882, in which also the religious school inspection had been attacked. ^5

The chronicle reports of many inspections, which, however, were generally satisfactory. Almost every year Laser reported who was newly admitted to the school at Easter and who left it. Readers also learn about local life. Laser reported, for example, on epidemics to which some children - including his own - died.

1882

On January 25, 1882, Laser received the order of appointment as teacher and cantor from the royal government in Kassel. On February 1st he was inaugurated by the pastor and local school inspector Sessler? and on February 2nd he was sworn in by district official Engelhard in Vöhl.

On January 24th the local school inspector visited the classes in religion and mathematics.

On June 15th, the local school inspector visited the classes for the second time and on this occasion informed that the teacher was not allowed to offer lessons beyond the scheduled classes.

On July 5th, from 8 to 11 a.m., the first real school examination was performed by the local school inspector, who expressed his full satisfaction.

On July 10th, the school inspector Meyer from Höringhausen repeated the examination.

On July 18th, "at exactly seven o'clock", the local school inspector checked the punctual start of classes.

On July 25th, the local school inspector checked the school chronicle and informed about the beginning of the 14-day summer vacation on August 7th.

On November 15th, the local school inspector checked student performance in reading and noted significant improvements among weaker students. He also warned against reading the Hessian school newspaper. He justified this with an article written in its edition 39/1882, in which the religious school inspectorate had also been attacked.^6

^5/6 Paul Arnsberg writes in " The Jewish Communities in Hesse" that Laser had been a teacher at the Jewish school since 1885, temporarily until 1895, then permanently. The school chronicle proves that this is not correct. Laser was therefore the successor of Salomon Bär, who died in June 1881. Between the death of Salomon Baer and the start of Joseph Laser's service on February 1st, 1882, the Jewish children were taught in the Protestant school by teacher Sandlos, who received a gratuity of three hundred marks for this according to the "Order of the Royal Government for Schools and Churches in Kassel". (Source. School Chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archives, Jerusalem , 8273/3)

1883

On January 26th, he registers the birth of his daughter Mathilde Emilie on January the 19th at the registry office.

On April 17th, Pastor Pflug performed his first school examination as the new local school inspector.^7

1884

On July 8th, Pastor Pflug again inspected the school. On July 15th, High School Inspector and Dean Meyer from Höringhausen came and expressed his satisfaction with the performance of the students. ^8

1885

On Sunday, March 8th, diphtheria spread among the teacher's children. On the basis of a ruling by the Royal Administrative Office, classes were canceled until April 13. ^9

On October 1st - during the autumn vacations - an epidemic of whooping cough was reported in Vöhl, which affected all the schoolchildren. It was not until Monday, November the 23rd, that classes could be held again. Laser writes in the chronicle that during the entire school year until spring 1886, the children repeatedly fell ill with whooping cough and the lessons suffered greatly as a result. ^10

1886

On Thursday, July 15th, a pre-examination was carried out by Pastor Pflug, and on July 19th head school inspektor Meyer returned, who subsequently voiced his satisfaction.

In the summer of that year, the south side of the school building was completely renovated. During this time, classes were held in the synagogue. ^11

1888

On Tuesday, September 18th, the school inspection by Dean Meyer took place. He again stated that he was satisfied with the school. ^12

1889

Around Christmas, there was an influenza epidemic throughout Europe, which also sickened numerous children in Vöhl. In addition, there were cases of other childhood diseases, especially measles. The school therefore remained closed for seven weeks. ^13

1890

In September 1890, family members fell ill with diphtheria. The fall vacation was therefore extended by a few days. ^14>

received a bonus of three hundred marks". (Source. School Chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archives, Jerusa-lem , 8273/3)

^7 Source. School Chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archive, Jerusalem , 8273/3.

^8 Source. School Chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archive, Jerusalem , 8273/3

^9 Source. School chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archive, Jerusalem , 8273/3

^10 Source. School chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archive, Jerusalem , 8273/3

^11 Source. School chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archive, Jerusalem , 8273/3

^12 Source. School chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archive, Jerusalem , 8273/3

^13 Source. School chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archive, Jerusalem , 8273/3

^14 Source. School Chronicle, The Jewish Historical Archive, Jerusalem , 8273/3

Joseph Laser was the first person that we know of who lived in the new building. He worked at the school for many years. Laser came from Hattenbach near Trier and moved to Vöhl with his wife and one son. His wife had several miscarriages and died in 1885 after giving birth. Laser married for a second time, and every other year his wife gave birth to a child. He died of heart failure at the age of 58 in 1906, just as he was about to give a toast on the loss of one of Abraham Blum's daughters. His funeral is reported in detail in the Corbacher Zeitung. The Jewish community formulated an obituary for the teacher who had held his office for almost 25 years. His achievements as a teacher and precentor were honored, the Jewish teacher Plaut from Frankenberg held the eulogy, and the Protestant pastor Kahler also spoke words of commemoration as school inspector; Dignitaries from Vöhl also took part in the funeral service.

The Jewish school from 1881 to 1925

The schoolroom was located on the marked floor. The entrance was located at the other side of the building. The door with the round arch probably connected to the mikvah in this building. In the first quarter of the 20th century a bakery was opened here.

During the time of Laser, there was a conflict with the political community about the financing of the bakery. The law stipulated that the community had to support the Jewish school if it also supported the Christian school. At the same time, however, a limit of 12 students was set, while in 1909 there were only 8 Jewish children attending the elementary school. The community no longer wanted to pay the contribution of 200 RM. Nevertheless, the superior authority demanded the continued payment of the fees.

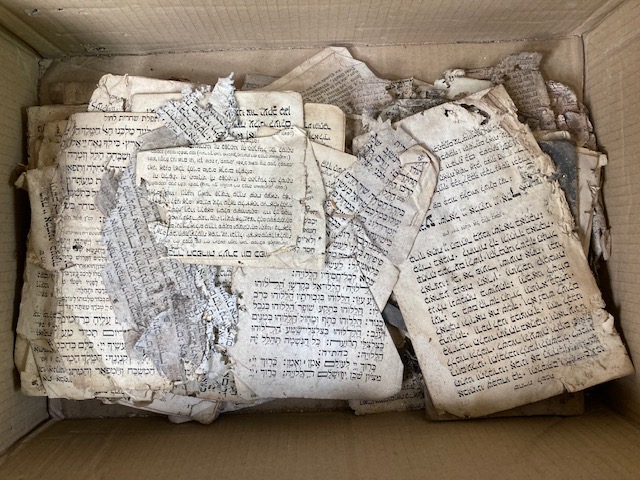

Joseph Laser began to write a school chronicle, which his successors continued until 1920. This chronicle is now in the Central Archives of Jewish History. It probably got there along other books of the Jewish community of Vöhl during the period of the nazi regime.

This chronicle - later continued by teacher Louis Meyer - gives a good insight not only into everyday school life, but it also informs about other aspects of public life in Vöhl.

In 2006, a great-grandson of Joseph Laser contacted the author of these lines. He had become aware of the website of the Förderkreis. He informed about the fate of his family after they had moved away from Vöhl. His grandfather Leopold, who had been born in Vöhl as the youngest child of Joseph Lasers' first wife, had trained as a merchant in Westphalia. He married, and his wife was blessed with three children; in early March 1943, the couple and their youngest son were deported to Auschwitz and killed. Kurt, the eldest son, was hold captive in the Dachau concentration camp after the Pogrom Night on November 9th. After his release, he emigrated to Sweden, where he lived until his death. Leopold's daughter Karla fled to Palestine in 1936 at the age of 16 with the support of a Jewish youth organization. She married, gave birth to a daughter and a son, and in 1958 the couple moved with their son to Germany, where the family initially lived in Frankfurt, moving to Hamburg after the father's death.

Another great-granddaughter of Laser, in fact a step-granddaughter of his daughter Johanna, contacted the author in May 2010 and informed him about her grandparents. In particular, she sent a picture of the gravestone of her great-grandfather, the teacher Joseph Laser, which to date shows us the only photographic evidence of the new fence around the Jewish cemetery, financed by donations between 1904 and 1911.

What was it like in the schools of Korbach

As already mentioned, several sons of Jewish parents from Vöhl went to the secondary school in Korbach. As early as the 19th century, we know of quite a number of Jews from the religious community who were educated there for a few years and left after completing and graduating from it.These included, for example, Leopold Külsheimer from Basdorf, son of Bendix Külsheimer, as well as Hermann Schönthal, son of Emanuel Schönthal, a horn turner from Vöhl; he was even one of the children of poorer families who afforded higher education for their children. Bernhard Frankenthal, Albert Katzenstein, almost all male Rothschilds, Ferdinand Kaiser or Louis Blum attended the schools in Korbach. Several of them stayed there only a few years to continue their education elsewhere; others left early to start a commercial apprenticeship. The Abitur does not always seem to have been the goal. Erna Katzenstein (Mainz) or the children of Ferdinand Kaiser (Marburg) attended higher schools outside the region.

During the First World War and the Weimar Republic

From 1910 Louis Meyer worked as a teacher in the Jewish school until its end in 1925. In the first years (1912, 1915) he appears several times on donation lists of the Jewish community in favor of the improvement of the synagogue. ^15

1914

April: Meyer is finally hired as an elementary school teacher. The synagogue community pays his salary.

At the outbreak of war at the beginning of August 1914, the Jewish school is dissolved or merged with the Protestant school, the second teacher (Jonas) is drafted and Meyer is hired as the second teacher in the Protestant school. He and his colleague have to teach in Obernburg on 2 weekdays.

^15 Source: fonds 1.75 A Vöhl in the archive of the "New Synagogue Berlin - Centrum Judaicum" Foundation

1915

Meyer is drafted in November 1915 (Landsturm with weapons).

1919

When he returns in February 1919, he is again employed and paid as 2nd teacher of the Protestant school; as of March, the Protestant and Jewish schools are again separated.

June 30th: Meyer performs the church wedding of Hugo Davidsohn and Ida, née Frankenthal.

On November 10th, he is given leave of absence; the 5 Jewish students are transferred to the Protestant school.

Due to the small number of children, teacher Meyer has difficulties in having the parents' council elected. In February, the school authority in Frankenberg signals that no objection will be made if mothers are also elected, especially since this is possible anyway according to the election regulations.

One of his sons needs an 8-day brine bath cure. Meyer applies to school inspector Broh-mer in Frankenberg for vacation for himself and his son, so he can accompany him to Sassendorf. The request is granted. ^16

1921

The " salary of the holder of the teacher's position in Vöhl, which is connected with religious service" is 1000 Mark.

Teacher Meyer has 5 students, one boy and four girls.

The income of the teacher:

the initial fixed salary 21700 M

the local bonus 2400 M

Compensatory allowance including emergency bonus 4820 M

Value of the home 175 M

Value of the garden 5 M ^17

1922

June the 27th: The district of Frankenberg informs the board of the Jewish community that the teacher is no longer obligated to serve in the cult office. The school board of the district requests the number of school children that can be expected in the next 5 years.

The list of teacher Meyer:

1922: 6 children, 3 of them are his children; 1923 and 1924: the same; 1925: 5 children, 192: 4 children; three of them are children of the teacher; a first new enrollment was only to be expected again in 1927. ^18

^16 Source: The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem.

^17 Meyer himself gives this information on a form of the Prussian government. Source: The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem

^18 The child to be enrolled in 1927 probably refers to Walter Mildenberg, born in 1921.

The number of Jews in Vöhl became smaller and smaller, and with it, of course, the number of school-age children decreased. During the First World War, the Jewish and Christian schools were temporarily combined, since one of the teachers of the Protestant school as well as the Jewish teacher Julius Flörsheim were drafted. After the war they were separated again. Flörsheim received an offer from a Frankfurt school and left Vöhl. Meyer stayed, but he had to teach mainly his own children.

The available sources portray Louis Meyer as a difficult man to characterize. On one hand, he seems to have been a person who did not always get along well with others. On the other hand, he was a very political person, who especially stood out in his confrontation with Nazis. During his years at Vöhl, however, nothing is known of any political activity.

The effects of a conflict with the old Karoline Rothschild, who after the death of her husband Moritz probably moved back to the birthplace of her husband, even became the subject of reporting in the Corbacher Zeitung. There it is reported that the widow Rothschild had left a barrel with freshly washed laundry outside overnight. And when she wanted to bring the clothes back in the next morning, she was horrified to discover that someone had tainted the laundry with aniline ink which led to the cooking linen being turned blue. The newspaper criticized the rude manners and asked who could do such a thing to an old woman. For Richard Rothschild, the old lady's grandson, the guilty person was absolutely clear when the incident was mentioned to him in 1999. "That was teacher Meyer," he said; Meyer had not gotten along with anyone, including his family.

And indeed, we know today that Meyer was probably a man who kept to himself and who found it very difficult to establish closer relationships with others. In 1925 he moved to Korbach as a teacher, left the Jewish community there, survived the Holocaust -probably in East Germany- and then changed back to the Jewish faith. His wife and children had left him; she went to Israel, the children were in America. And thus Louis Meyer died a lonely old man in Cologne in the 1970s.

Here, however, it should be noted that Meyer, like his predecessors, also performed ritual duties in the religious community. For example, when he married Ida and Hugo Davidsohn. But in the 1920s it was no longer possible to get the Jewish teachers to participate in the services. In 1921, the teacher who also provided religious services in the synagogue received 1000 Reichsmark.

Education for Jewish children in the Third Reich

Which Jewish children in Vöhl were still required to attend school after 1933? First there was the youngest of Hermann Mildenberg's daughters, Charlotte. Then there were the two children Walter and Ursula Mildenberg, born in 1920 and 1924. Both Charlotte and Walter Mildenberg finished school in their second year after Hitler's appointment as Reich Chancellor. Ursula Mildenberg shared that Walter, as an athlete recognized by teachers as well as his peers, had no difficulties in school. His cousin Charlotte followed the example of her sisters after leaving school and went abroad to work as a domestic worker. Walter completed his training as a butcher outside of Vöhl in keeping with tradition.

In the mid-1930s, Ursula Mildenberg was the only Jewish student at the school on the Schulberg. She has almost only bad memories of this time. She was teased a lot, sometimes accused of theft, and sometimes even beaten. It was particularly bad when her non-Jewish peers had race studies in the first lesson and she joined them in the second lesson. During the breaks, she did not stay at school or in the playground, but went to the Frankenthal houses. The teachers hardly paid any attention to her; she learned very little. At the end of 1937, she emigrated with her parents to the USA via Frankfurt, where they left her grandmother with relatives.

For Günther Sternberg, who was only six years old and the youngest Jewish child in Vöhl, this meant that he now had to go to school in Frankfurt. Israel Straus, a little older than Günther and coming from Altenlotheim, reports in a letter that he attended the Jewish Philanthropy School in Frankfurt together with Günther Sternberg. They had initially lived in a Jewish children's home run by the Flörsheim-Sickel Foundation. He and Günther did not go to the same class and did not sleep in the same room, but they often played together and always went home together during the vacations, he to Schmittlotheim and Günther further to Herzhausen. After the summer vacations in 1940, they had to move to the Jewish orphanage, since the children's home had been occupied. According to his recollection, in October 1941 some children, including he and Günther Sternberg, were sent to their parents to be deported. Israel Straus and his family were taken to the Riga ghetto in December 1941. Some other children of the Philanthropy School would have belonged to this transport, but Günther was not among them.

As we now know, Günther Sternberg and, according to witnesses, his parents were also deported - although a few months later - first to Wrexen and from there to the East. Günther Sternberg and his mother were probably gassed in Sobibor at the beginning of June 1942, while his father had to do a labor worker in the Majdanek concentration camp and died in September of the same year.

In May 2005 we found in an archive in Jerusalem a school chronicle and teaching records from the early 20th century. These documents have not yet been fully evaluated. After this is done, we will certainly be able to add some interesting chapters to this essay.

The only surviving picture of the interior of the synagogue; early 1930s Photo: Ernst Davidsohn (1921-95) Donated by C. Baird (descendant of the Frankenthal family from Vöhl)

The only surviving picture of the interior of the synagogue; early 1930s Photo: Ernst Davidsohn (1921-95) Donated by C. Baird (descendant of the Frankenthal family from Vöhl) Taken from: Thea Altaras, Synagogues and Jewish Ritual Immersion Baths in Hesse - What has happened since 1945?, Darmstadt 2007

Taken from: Thea Altaras, Synagogues and Jewish Ritual Immersion Baths in Hesse - What has happened since 1945?, Darmstadt 2007 The room is photographed.

The room is photographed. And measured.

And measured. The rest of the work is done on the computer.

The rest of the work is done on the computer. Firstly, the current furniture is removed from the room.

Here it already has a floor covering modelled on the old one.

Firstly, the current furniture is removed from the room.

Here it already has a floor covering modelled on the old one. Then it is refurnished.

Then it is refurnished.

One of the vault columns

One of the vault columns Stairs to the mikveh with shelf

Stairs to the mikveh with shelf Shaft mikveh

Shaft mikveh

A woman purifies herself in a mikvah, while her husband waits for her in bed.Germnany 1427/28

A woman purifies herself in a mikvah, while her husband waits for her in bed.Germnany 1427/28 Cleaning of dishes in the mikvah.

Cleaning of dishes in the mikvah.

Arolser Str. 8

Arolser Str. 8 Door to the basement with mikvah?

Door to the basement with mikvah?

Photos: Kurt-Willi Julius, Schulstandorte in der Arolser Str, 8 und Mittelgasse 9

Photos: Kurt-Willi Julius, Schulstandorte in der Arolser Str, 8 und Mittelgasse 9  The school constructed in 1827 in the Mittelgasse 9, Photo: Kurt-Willi Julius 2004)

The school constructed in 1827 in the Mittelgasse 9, Photo: Kurt-Willi Julius 2004) Haus Rothschild, Arolser Str. 8, Photo: Kurt-Willi Julius

Haus Rothschild, Arolser Str. 8, Photo: Kurt-Willi Julius